Executive Summary

Pillar 9: Health, Safety and Environmental Protection Regulation presents a model regulatory framework designed to ensure that the biogas industry upholds recognised best practices when it comes to health, safety and environmental protection during operation.

It provides comprehensive oversight, enforces strict safety protocols and mandates responsible environmental practices, such as methane emission controls and waste management. Additionally, the framework can be adaptable, encouraging continuous improvement and the adoption of innovative technologies. By adopting the recommendations listed in this pillar, governments can foster a thriving biogas sector that prioritises safety, environmental protection, and long-term sustainability.

Conclusion

As with other energy operations, running a biogas plant requires diligent regulatory oversight to safeguard workers, the public, and the environment. This pillar highlights the critical aspects that regulatory bodies must monitor to ensure industry growth aligns with sustainable development goals.

PILLAR 9: Health, Safety and Environmental Protection Regulation

Introduction

“A safe and healthy working environment is not only a fundamental principle and right at work but also an essential requirement for fostering sustainable and inclusive economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.

– International Labour Organisation

Each year, 2.6m people die globally from workplace-related ill health. Over 395m workers worldwide have sustained a non-fatal work injury. 1 The agriculture, construction, and waste and recycling industries have higher rates of fatalities and significant injuries.

There are many challenges in running and operating a biogas plant safely. However, with the proper controls in place and competent staff and management systems, there is no reason for a biogas plant to be a dangerous place when it comes to health, safety and the environment.

9.1. Develop a biogas industry risk profile

Given the multifaceted nature of the anaerobic digestion (AD) industry, the risk profile of the industry is a combination of risk factors from the following industry sectors: waste and recycling; onshore gas production; agriculture (crop feedstocks and liquid/solid digestate); and construction (design, build and maintenance of assets).

A comprehensive risk profile of the industry must be developed at the national level to monitor and benchmark performance and protect people and the environment.

EXAMPLE

In the UK, sector-based health and safety risks, guidance and data are made available by government agencies for the industry to use. 2 3 4 5

9.2. Recognise climate change as a health, safety and environmental risk

Climate change is the greatest threat to the environment and human existence. There must be a 42% cut in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 to limit warming to 1.5°C. 6

It is essential to find solutions to reduce the impact and effects of climate change on people and organisations around the world. This can only be achieved through the clear, joined-up actions of industries working towards a common aim in reducing emissions globally.

Recognising climate change as an immediate risk to businesses and workforces at an organisational level can help translate national policy into organisational action.

9.3. Adopt international approach and standards

While regulations and their applications vary from one nation to another, there are recognised international standards set by the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) that determine the requirements for good occupational health and safety and environmental management. 7

These standards adopt a continuous improvement model and outline a process approach, which means managing business activities as a series of interrelated processes. 8 Risk assessment as part of this approach is a fundamental requirement for organisations to identify and control specific risks throughout the plant’s lifecycle, from design, construction, operation and maintenance to decommissioning.

Regional and internationally harmonised technical standards can be applied to equipment and products. These can be used to demonstrate conformity with national legal requirements while also allowing the import and export of technology.

EXAMPLES

ISO45001 is an international standard that specifies requirements for occupational health and safety management systems. 9

ISO14001 provides a framework for organisations to design and implement an environmental management system, and continually improve their environmental performance. 10

CE marking in Europe and UL labels and marking in North America provide equipment safety certification for these regions.11 12

9.4. Take an integrated approach to governance

Several integrated approaches have gained prevalence over the last decade, including Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Environmental Social Governance (ESG). These approaches have good corporate governance, health, safety, welfare, and environmental stewardship at their heart, and they are adopted mainly by big corporate entities where many assets or sites may be involved.

Figure 1 typically shows the pyramid of requirements that set and control organisational good governance regarding Health, Safety and Environmental Management. Taking a top-down approach, legislation from the government and company constitution govern the organisation. These statutory requirements are reflected in the board charter. These are interpreted into policies, procedures and supporting documents for implementation at the organisation level. 13

Figure 1. Pyramid of Requirements for Good Organisational Governance for Health and Safety Management

9.5. Reinforce safety in organisational culture

Good workplace management systems require more than a set of documents to be effective. The right culture must be created to ensure the identified requirements can be met. Culture can be simplistically defined as “the way we do things here” – this is encoded in management standards adopted and processes implemented for safe work.

The maturity of an organisation’s safety culture will depend on several factors, including national laws and enforcement of regulations; country and regional culture; attitudes to safety and the environment; education and awareness; and management aims, objectives, values and priorities.

The key parts of a strong safety culture are defined in sections 9.5.1–9.5.4.

9.5.1. Communication

Management and workers must have clear communication channels to escalate issues, report incidents, share information from management to the workforce, and vice versa. Communication must be clear, timely and fully understandable. Cultural surveys and workforce engagement surveys can be used to identify issues and concerns. These can be repeated once actions have been taken to address identified issues.

9.5.2. Control

Control can be demonstrated through good management practices and a management system that effectively delivers the intended outcomes required by the organisation. This can be through setting clear policy; planning and implementing policy objectives; organisation of the workforce roles; measuring performance; and auditing and review of arrangements.

9.5.3. Cooperation

All associated parties must work together to reach the objectives of a safe working environment and high production output. This requires the right attitudes and behaviours from management and the workforce.

9.5.4. Competence

This can be defined as a combination of the required skills, knowledge, aptitude, training and experience. A competent workforce is key to ensuring safety and productivity at a biogas plant. Operators must have the majority of these attributes as part of a competency management programme within the management system.

9.6. Incorporate hierarchy of controls in safety policies and regulations

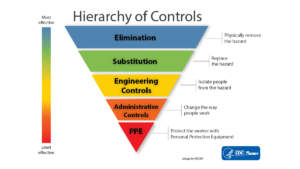

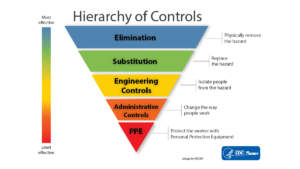

For safety, the approach to risk management should consider the nature and effectiveness of control measures, elimination being the most effective and personal protective equipment (PPE) the least, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Hierarchy of Control Measures for Health and Safety

9.6.1. Elimination

Remove the hazard entirely to eliminate the risk of exposure. This may not always be possible due to process and business constraints. It should be considered first in the process of risk assessment controls and risk reduction. Good health and safety practice is to reduce risk to ‘As Low As Reasonably Practical’ (ALARP). 14

9.6.1. Substitution

Replace hazardous materials, processes or equipment with less risky alternatives where possible. Risk is reduced with substitution, but there may be significant challenge to implementing substitution as it may, in the case of equipment and machinery, require a business case and return on investment to be considered before achieving the desired state.

9.6.3. Engineering controls

Modify the workplace or equipment to reduce exposure, e.g. ventilation systems, barriers. These are generally effective as long as the controls are maintained, effective in design and not bypassed.

9.6.4. Administrative controls

Implement policies, procedures and training to manage risks, e.g. work schedules and methods and signage. This can be effective, but it relies on the correct application and is prone to human error, communication issues and lack of understanding. Behaviours, such as feeling pressure to complete the job quickly or bypass defined safe methods, can also be an issue.

9.6.5. Personal protective equipment (PPE)

This is the least effective control measure as it fails to reduce the exposure or danger, only protects the individual, and does not provide collective protection of the workforce. PPE is only effective if used correctly, maintained and replaced at required intervals. PPE should be used to protect from residual risks, not as a primary solution to control potential workplace hazards.

EXAMPLE

The United States Occupational Safety and Health Administration (US-OSHA) provides extensive guidance on controlling exposure. 15 It further provides a worksheet to demonstrate its implementation. 16

9.7. Ensure competency of staff and contractors working on-site

The provision of adequate information, instruction, training and supervision is critical to all businesses, for both compliance and business reasons.

Adequate information, instruction, training, supervision and competency requirements should be referenced in legislation regarding health and safety management. This is a legal “test” when ensuring whether health and safety arrangements are “suitable and sufficient”.

9.7.1. Information

Health, safety and environmental information can be provided in many forms, including posters, leaflets, noticeboards, company reports, toolbox talks, etc. In practice, a dedicated space where all employees can see information on health, safety and environmental issues, such as a noticeboard or intranet, is a great way of communicating information.

EXAMPLE

In the UK, it is law that organisations employing five or more people must display a “health and safety at work” poster published by the UK Health & Safety Executive (HSE) that defines employers and employee duties, and relevant health and safety contact information. 17

9.7.2 Instruction

Instruction can form part of verbal or written communication to define management requirements for working in a safe manner. These arrangements should be captured in the company safety policy, clearly identifying roles, responsibilities and arrangements when it comes to instruction.

9.7.3 Training

Training must be relevant to the risks posed and consider the employees’ experience. Young and inexperienced workers will need greater training than more experienced workers. It is important that any changes to training standards or requirements are communicated to all workers so that everyone’s competencies remain up to date. Trainers must demonstrate competence with qualifications and experience.

EXAMPLE

For health, safety and environment matters this might include a suitable qualification from a recognised provider such as the National Examination Board in Occupational Safety and Health (NEBOSH) in the UK and Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) and Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment (IEMA) globally. Training may be provided by experienced staff, or specialist providers can offer bespoke training courses relevant to the biogas industry. Training and education qualification in the UK is provided according to the education standard under the Award in Education and Training (AET).

9.7.4. Supervision

Supervision of the workforce is always required. The level of supervision and type will depend on the level of experience of individuals and will increase or decrease depending on the task and the risk involved. This should form part of the risk assessment for high-risk tasks.

9.7.5. Competency

Each organisation must implement a robust safety programme covering key topics, including the operation of the AD plant and specific tasks that staff may be requested to do, such as mobile plant operation, maintenance or sampling. A set level of health and safety training that provides the basics of hazard identification and risk assessment must be delivered to all site staff.

All staff and contractors must be subject to competency checks before being allowed to work on site. All visitors must be given a site induction covering the key hazards before they are allowed to enter operational areas.

Each site must be run by a ‘competent person’ or technically competent manager.

Competence can be achieved through successfully completing training and assessment from a nationally or internationally recognised and accredited health and safety organisation.

EXAMPLE

WAMITAB scheme, run by the Chartered Institute for Waste Management in the UK, offers training and assessment to individuals who want to have the required knowledge to operate waste management facilities. 18

The Competence Management System, developed by Energy & Utility Skills is a technical scheme that enables operators to demonstrate technically competent management of their permitted activities. 19

Advice on implementing a competency management system is available from EU skills. 20

9.8. Require a documented health and safety policy

It is critical that all regulators require health and safety policies and related documents be in place, to ensure the company has a policy.

Organisations that employ five or more people must be required to document a health and safety policy. The policy should be composed of three parts: a statement of intent; organisational roles and responsibilities; and key arrangements for implementation.

EXAMPLE

The UK has made it mandatory for organisations employing more the five employees to prepare and implement a health and safety policy. 21 An example UK HSE policy is also available. 22

9.8.1. Statement of intent (SOI)

The SOI is the top leadership commitment to ensuring safety in the organisation. It outlines the objectives and aims of the business to ensure that health and safety (and environmental management) obligations are met. It is normally signed by the top-level executive in the business and reviewed annually for accuracy and effectiveness.

EXAMPLE

FGS Agri’s statement of intent for their biogas facility is publicly available.23

9.8.2. Roles and responsibilities

Roles and responsibilities are normally defined in the company organisation chart, or organogram, showing authority structures and roles. Secondary roles, such as fire wardens and first aiders, can also be defined in the organogram. Further definition can be added via a delegated authority structure, a Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed (RACI) matrix, a job description/role, and standard operating procedures.

The safety manual may explicitly define the role requirements in terms of safety requirements, using a combination of the techniques above.

Roles and responsibilities must be clearly communicated so that everyone understands who has what level of authority for health safety and environmental management decisions.

9.8.3. Risk management arrangements

The arrangements section of the policy will define the specifics of what must happen to ensure the aims and objectives of the policy are achieved. What are the key arrangements that must happen to ensure that health and safety are suitably managed? This can be achieved through a policy manual or additional references to other policies and key procedures.

EXAMPLE

The international in ISO 14001 and 45001 standards covers all elements of the operational activities.

9.8.4. Incident and hazard reporting

For businesses to understand what is happening in workplaces, they must have a suitable hazard and incident reporting system in place that includes details on when information must be passed to regulators as detailed in 9.8.4.1 and 9.8.4.2.

9.8.4.1. Hazard reporting

Hazard reporting is important to ensure that anything in the workplace that has the potential to cause harm is controlled. Data captured from hazard reporting can inform where there are risks that need greater control or review of current risk controls.

9.8.4.2. Incident reporting

Certain incidents, health and safety as well as environmental, must be reported due to regulatory requirements. Other incident reporting is part of good governance practices. It also plays a key role in data collection, lessons learned from accidents and incidents, and improvement of processes as a result. Each organisation should define the categories of incidents that require reporting.

EXAMPLE

A template of an incident/accident report form is available from the UK Government. 24

9.8.5. Emergency arrangements

It is critical that emergency arrangements be considered as part of the health and safety policy arrangements. These should include:

- emergency planning and response

- disaster recovery

- business continuity.

Emergency plans should be practised, e.g. fire drills, and logs and records kept. Practising emergency response is key to ensuring that there is the right response to emergency events.

Disaster recovery is based on the set of arrangements required to recover from events that could affect the business. This could be a major spill or pollution event, or a major accident or injury. The arrangements may need to assess media coverage, protocols, and who takes charge to return to normal operating conditions.

Business continuity should focus on the arrangements required to recover from major events. Using home-based working during the coronavirus pandemic is a good example of an effective business continuity arrangement.

EXAMPLE

In the UK, guidance on emergency procedures is available from the UK HSE. 25

9.8.6. Managing process change

Management of change is an integral part of process safety. Any changes proposed to the plant or control systems must go through a rigorous process, including a design proposal that considers how the change will affect the plant, operators, health and safety, environmental requirements, or other legislation. All proposals must be considered via a structured process and detail the benefits to the business that the change will achieve.

EXAMPLE

The UK HSE have a management standard for change. 26

9.9. Require an environmental policy to be developed

As with health and safety policies, an environmental policy statement should reflect the organisation’s intent to minimise pollution. ISO 14001:2015 specifies:

AD plants should establish, implement and maintain an environmental policy that, within the scope its environmental management system:

- is appropriate to the purpose and context of the organisation, including the nature, scale and environmental impacts of its activities, products and services

- provides a framework for setting environmental objectives

- includes a commitment to the protection of the environment, including prevention of pollution and other specific commitment(s) relevant to the context of the organisation

- includes a commitment to fulfil its compliance obligations

- includes a commitment to continual improvement of the environmental management system to enhance environmental performance.

The environmental policy shall be:

- maintained as documented information

- communicated within the organisation

- available to interested parties.

Other specific commitments to protect the environment can include sustainable resource use, climate change mitigation and adaptation, and protection of biodiversity and ecosystems.

In terms of sustainability a “cradle to grave” approach must be taken. All elements of the environmental impacts and aspects, from design to decommissioning, must be incorporated into the environmental impact of a biogas plant. Environmental management objectives and programmes must look at the reduction of environmental impact through policy; for example, a travel policy that supports or incentivises electric vehicle use over internal combustion engine cars.

Integration and logistics with biogas plant machinery and HGVs is possible and must be considered as part of design if there is the need for road haulage of biogas, digestate or feedstocks.

A biodiversity net gain of 10% or more from pre-construction levels should be applied to new projects. Constructing a biogas plant requires significant material impact: concrete, steel and soil removal are all required to some extent. Suitable planting of diverse and native species, such as hedges to provide natural green barriers and create a pleasant environment and habitats for insects and wildlife, must be considered. Well-thought planting can provide screening, security and nature benefits to offset the environmental impact of construction.

The sustainability of feedstocks must be considered at the time of developing a new site. This is discussed in detail in Pillar 2: Feedstock Policy.

Wherever possible, an integrated approach to health, safety and environmental requirements must be taken, as they are closely related.

9.10. Develop and enforce an environmental permitting process

Most countries and territories have some version of environmental legislation that applies to AD plants. Developing a robust environmental permitting system is key to mitigating and managing risk to the environment.

This is discussed in detail under Pillar 7: Environmental Permitting.

9.11. Require the implementation of an Environmental Management System (EMS)

AD plants must operate with an environmental management system (EMS). The EMS could be integrated with other systems as part of the Integrated Management System (IMS) but must contain information about the land the site is built on and how the facility is operated and maintained. The EMS should align with international standards such as ISO 14001 and determine how the plant will operate without harming the environment. Arrangements must be defined to demonstrate how the facility will prevent air, soil or water pollution around the site and minimise any disruption to local receptors.

The plant must have a maintenance programme in place to prevent leaks or emissions from gas, digestate or other substances used in the process. Any fugitive emissions should be recorded, and in some areas must be reported to the local enforcing authority.

An EMS must address health, safety and environment information such as:

- air quality

- containment arrangements for the site

- document control arrangements

- documented review arrangements

- ecological receptors

- environmental policy

- feedstock arrangements

- geology and hydrology

- human receptors

- infrastructure and environmental sensitivities

- monitoring arrangements for process

- organisation charts and company profiles

- process description

- scope of the system

- site description

- surface water

- training, awareness and competence.

Permits specify limits for emissions, monitoring methods and reporting requirements among local requirements, and environmental regulators will conduct regular site visits to ensure compliance.

Environmental regulators are increasingly focused on the safety of AD plants alongside the environmental impact. They will examine any fire, dangerous substances and explosive atmosphere risks and ask for preventative maintenance schedules to be submitted. Regulators often want to see evidence of an EMS or IMS in place that meets their requirements as a regulator. Each site must be run by a ‘competent person’ or technically competent manager.

EXAMPLE

Guidance on Environmental Management Systems is available from the UK Government and from the US Environmental Protection Agency, 27 28

ISO14001 provides a framework for organisations to design and implement an Environmental Management System and continually improve their environmental performance. 29

An example of an Environmental Management System for a biogas plant is available for reference.30

9.12. Require incident reporting and publish data to develop industry best practice

Permitted environmental sites should be required to report pollution events as part of permit notification to the environmental regulator. Similarly, certain incidents and dangerous occurrences must be reported to the health and safety regulator in the country.

The data and information collected must be made available to the industry to benchmark and improve industry performance. It can be used by regulators to inform and strengthen health and safety regulations.

EXAMPLE

In the European Union, there is a legal obligation via Regulation 1338/2008/EC to report occupational accidents and diseases. 31

In the UK, the HSE regulates and requires report of incidents under the Reporting of Incidents, Deaths, and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations (RIDDOR). 32 Reports can be made online. 33

9.13. Create a safe and comfortable physical working environment

Ensuring that the physical environment and working conditions are comfortable, clean, tidy, organised and free from hazards can have a significant impact on employee well-being. Where the work is physical in nature it must be organised to ensure environmental factors, such as heat, cold, intensity and duration, are considered as part of an organisational risk assessment. Access to basic hygiene, welfare facilities, safe working conditions, PPE and management supportiveness all help to create a positive working environment.

EXAMPLE

US-OSHA provides guidance on heat exposure, cold weather, restroom and sanitation requirements, PPE, and other related topics. 34 35 36 37

9.14. Develop organisational well-being policies

Health (or well-being) is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, as defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO). It is not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. In essence, well-being is about thriving, not just surviving.

Taking this view into account, creating workplace policies for health and well-being must enable employees to thrive in their working environment. Many of these actions can be defined by company policy and are outlined in sections 9.14.1–9.14.3

9.14.1. Human resource policies and support programmes

Employee assistance programmes can incorporate health insurance, helplines and resources for managing health and well-being. Fair sickness and absence policies, family-friendly policies, diversity, personal data protection, and an equality and inclusion policy can all build a culture of trust and support in an organisation.

9.14.2. Mental health policies

WHO describes mental health as: “a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realise their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community. It is an integral component of health and well-being that underpins our individual and collective abilities to make decisions, build relationships and shape the world we live in. Mental health is a basic human right. And it is crucial to personal, community and socio-economic development.” 38

Mental health in the workplace has emerged as a critical issue globally, influencing productivity, employee well-being, and overall organisational health. The biogas industry, with its unique challenges and opportunities, is no exception. This section outlines the importance of mental health policies within the biogas sector, providing a framework for developing and implementing these policies on a global scale.

9.14.2.1. Assessment of needs

A thorough assessment of the specific mental health needs of employees within the biogas industry is the first step. This involves surveys, focus groups and consultations with mental health professionals to identify key stressors and areas requiring support. 39 These challenges and focus points are:

- The biogas industry can create high-pressure environments due to the nature of the work, which includes long hours at peak times, such as crop harvests, managing organic waste, maintaining biogas plants in breakdown scenarios to maintain production, and ensuring compliance with environmental regulations. This can lead to chronic stress and burnout if not properly managed.

- Workers in the biogas sector can be exposed to physical hazards, such as toxic gases, heavy machinery, and potential accidents. The stress associated with these risks can exacerbate mental health issues

- Many biogas facilities are located in remote areas, leading to potential isolation for workers. Social isolation can contribute to mental health problems such as depression and anxiety.

9.14.2.2. Creating a supportive environment

There are some policies and initiatives that can create a supportive work environment, including:

- implement training programmes to raise awareness about mental health, reduce stigma and equip employees with coping strategies 40

- where appropriate, first aid risk assessments can be updated to provide mental health first aid and first aiders

- provide access to mental health resources, such as counselling services, employee assistance programs (EAPs), 41 and mental health hotlines

- identify and promote policies that encourage a healthy work-life balance, including flexible working hours and adequate leave provisions

- designate trained employees as mental health champions to provide peer support and promote mental well-being initiatives within the company

- integrate mental health policies with existing safety programmes to ensure a holistic approach to employee health.

EXAMPLE

Extensive guidance on the development of mental health policies and programmes is available from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the UK HSE, the International Labor Organisation and the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. 42 42 44 45

9.14.2.3. Crisis management

Develop a crisis management plan that includes protocols for addressing acute mental health crises, ensuring that employees have access to immediate support and intervention when needed.

9.14.2.4. Regular review and improvement

Mental health policies should be dynamic, with regular reviews and updates based on employee feedback, changes in industry conditions and advancements in mental health research.

9.14.3. Stress policy

Stress can be defined as “the adverse reaction people have to excessive pressures or other types of demand placed on them”.

Workers feel stress when they cannot cope with pressures and other issues. Employers should match demands to workers’ skills and knowledge. For example, workers can get stressed if they feel they do not have the skills or time to meet tight deadlines. Providing planning, training and support can reduce pressure and bring stress levels down.

Stress affects people differently – what stresses one person may not affect another. Factors such as skills and experience, age or disability may all affect whether a worker can cope.

There are six primary areas of work design that can affect stress levels and must be managed: demands, control, support, relationships, role and change.

Employers should assess the risks in these areas to manage stress in the workplace. Where an individual employee has specific issues, reasonable workplace adaptations must be considered.

EXAMPLE

Guidance on implementing a stress policy is available from the UK HSE, the US Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and the European Commission. 46 47 48

9.15 Take into account human factors and ergonomics

Where there are humans there are human factors. Accident and injury rates are 18% greater during evening shifts and 30% greater during night shifts when compared to day shifts. 49

The UK HSE defines human factors as:

“Human factors refer to environmental, organisational and job factors, and human and individual characteristics, which influence behaviour at work in a way which can affect health and safety.”

Each facility must ensure that a robust management system incorporating the risks associated with human factors is considered during the planning, building, operating and maintenance of the facility.

This specifies:

- The job: including areas such as the nature of the task, workload, the working environment, the design of displays and controls, and the role of procedures. Tasks should be designed in accordance with ergonomic principles to account for both human limitations and strengths. This includes matching the job to the physical and mental strengths and limitations of people. Mental aspects would include perceptual, attention and decision-making requirements.

- The individual: including their competence, skills, personality, attitude and risk perception. Individual characteristics influence behaviour in complex ways. Some characteristics such as personality are fixed: others, such as skills and attitudes, may be changed or enhanced.

- The organisation: including work patterns, the workplace culture, resources, communications, leadership, and so on. Such factors are often overlooked during the design of jobs but have a significant influence on individual and group behaviour.

In other words, human factors are concerned with what people are being asked to do (the task and its characteristics), who is doing it (the individual and their competence), and where they are working (the organisation and its attributes), all of which are influenced by wider societal concerns, both local and national.

Human factor interventions will not be effective if these aspects are considered in isolation. The scope of what is meant by human factors here includes organisational systems and is considerably broader than the traditional views of human factors and ergonomics.

Human factors can, and should, be included within a good safety management system and so can be examined in a comparable way to any other risk control system.

EXAMPLE

The UK HSE guidance document gives useful information on controlling the risks from human factors. 50 51

Specific guidance on managing human factors such as fatigue are available from US-OSHA. 52

9.16. Identifying those at greater risk

Pregnant women and young workers require a greater duty of care than others because they are at greater risk at work when it comes to health and safety.

Certain chemicals can affect the unborn child and, therefore, greater controls must be in place to protect pregnant workers. Additionally, fatigue, stress and adaption to the work must be identified in a suitable and sufficient risk assessment.

For young people under the age of eighteen, lack of experience, physical capability, overconfidence and lack of awareness mean that a greater level of training and supervision is required.

EXAMPLE

Additional guidance is available from the HSE on the protection of pregnant workers, new mothers and young workers. 53 54

9.17. Manage substances hazardous to health

There are many chemicals, substances and mixtures used in the process of creating biogas that can cause health effects on the human body. If managed and controlled effectively the risk to worker health and safety can be minimal. However, it is key to ensure that the principles outlined in sections 9.17.1–9.17.4 are in place to reduce the risk of harm to workers and others.

9.17.1. Classification, labelling and packaging

There is a global standard for the classification, labelling and packaging requirements of chemicals. The system, “Globally Harmonised System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS)”, classifies chemicals by types of hazards and proposes harmonised hazard communication elements, including labels and safety data sheets. It aims to ensure the information on the physical hazards and toxicity of chemicals is available in order to enhance the protection of human health and the environment during the handling, transport and use of these chemicals. The GHS also provides a basis for harmonisation of rules and regulations on chemicals at national, regional and worldwide level, which is an important factor for trade facilitation. 55

These standards should be adopted and implemented across industries and sectors.

9.17.2. Risk assessment and management

The best practice for controlling substances hazardous to health is to adopt a risk assessment approach. The risks of substances hazardous to health can be effectively managed by:

- finding out what the health hazards are

- deciding how to prevent harm to health, or risk assessment

- providing control measures to reduce harm to health

- making sure they are used

- keeping all control measures in good working order

- providing information, instruction and training for workers and others

- providing monitoring and health surveillance in appropriate cases 56

- planning for emergencies.

EXAMPLES

Guidance and templates for conducting general risk assessments are available from the UK HSE. 57

Guidance on conducting a Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (COSHH) risk assessment is available from the UK HSE. 58

9.17.3. Control measures

Controlling exposure to substances hazardous to health should be based on the hierarchy of controls detailed in section 9.6.

EXAMPLE

In the US, exposure to chemical hazards and toxic substances are regulated by US-OSHA, which also provides extensive guidance on controlling exposure.59

9.17.4. Additional requirements for large quantities of stored chemicals

Consideration must be given to by-products from the AD process and the constituent quantities, mixtures and amounts of chemicals stored. Where large quantities of explosive or flammable chemicals, or those that pose a significant risk to the environment, are stored, additional safety requirements may be introduced.

Specific assessments and studies must be undertaken at the design stage of the biogas plant to ensure that adequate management controls and permits are in place before the plant is operational.

EXAMPLES

In the EU, Seveso III Directive lays down rules for the control of major-accident hazards involving dangerous substances. 60

In the UK, large quantities of dangerous substances are regulated through COMAH (Control of Major Accident Hazards) regulations. 61

In the EU, the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) regulates through COSHH. 62

9.18. Implement processes to eliminate virological and biological pathogens

Given that the biogas industry is based on the processing of organic matter, certain regulations and processes must be implemented to eliminate virological and biological pathogens.

9.18.1. Legionella

Legionellosis is a collective term for diseases caused by Legionella bacteria. It includes the most serious form, Legionnaires’ disease, as well as the similar but less serious conditions of Pontiac fever and Lochgoilhead fever. Legionnaires’ disease is a potentially fatal form of pneumonia, and everyone is susceptible to infection. People contract Legionnaires’ disease by inhaling small droplets of water (aerosols) suspended in the air that contain the bacteria.

The risk of legionella is increased in certain conditions:

- the water temperature in all or some parts of the system is 20–45°C, which is suitable for growth

- it is possible for breathable water droplets to be created and dispersed, e.g. aerosol created by a cooling tower or water outlets

- water is stored and/or recirculated

- there are deposits that can support bacterial growth providing a source of nutrients for the organism, e.g. rust, sludge, scale, organic matter and biofilms.

The industry must require the risk assessment, monitoring and control of legionella in AD water supply and pipework systems to prevent exposure to people working in these environments.

EXAMPLE

Technical guidance on standards, prevention, control and outbreak response are provided by US-OSHA in the US, the HSE in the UK and the ESCMID Study Group for Legionella Infections in Europe. 63 64 65

9.18.2. Weil’s disease and leptospirosis

The risk of presence of leptospirosis and Weil’s disease is linked to areas where rodents are or have been present. Work is considered higher risk where there is evidence of rodent infestation.

The risk is increased in AD operations as feedstocks can attract vermin. Good pest-control techniques and landscape maintenance must, therefore, be in place, as well as good industrial hygiene practices and procedures.

PPE requirements must be determined through risk assessment, and adequate facilities for welfare must be provided for cleaning, washing and food preparation.

EXAMPLE

Guidance on control measures that should be implemented are available from HSE in the UK. 66

9.18.3. Bioaerosols

Bioaerosols are a complex mixture of bacteria, fungal spores and other fragments of biological origin that are suspended in air. Bioaerosols can interact with living systems through infective, allergenic and/or toxic mechanisms. Prolonged and repeated exposure to these can lead to health conditions such as asthma, hypersensitivity pneumonitis and gastrointestinal disorders.

At a biogas plant, micro-organisms naturally present in organic waste, such as domestic, garden and food waste, multiply quickly when stored, especially in warm and moist environments. There is a risk that bioaerosols will be generated during the handling and processing of organic waste, particularly when this is energetic.

Regulations governing bioaerosols in workplaces must include bioaerosol exposure assessment and risk management, measurement and threshold limits for exposure, and enforcement of prevention and control measures.

EXAMPLE

Regulations, standards and guidance specific to bioaerosols are developed and enforced in the EU. 67

The Waste Industry Safety and Health (WISH) forum provides information on ensuring safety when working with bioaerosols. 68

An example of a bioaerosol risk assessment for a biogas plant is referenced. 69

9.19. Regulate handling and processing of animal by-products (ABP)

Animal by-products (ABPs) are animal carcasses, parts of animals, or other materials that come from animals but are not intended for human consumption. These are commonly processed at biogas plants. ABPs are biological agents that present a risk to human health; when coming into contact with ABPs workers are at risk from numerous infections spread by Campylobacteria, E. coli and Salmonella, for example. The absence of biosecurity protocols can also lead to cross-contamination entering the food chain and harm to the environment.

ABPs are divided into high-, medium- and low-risk categories. Regulatory requirements, including permitting and the biosecurity controls needed for compliance, are different for each category. Given the risk posed by ABPs, their handling must be regulated with monitoring and enforcement, and non-compliance deterred with possible fines and sanctions.

Beyond compliance, and to ensure the safety of workers, it is critical for each facility to have a policy in place to control the risks from ABPs, which should be equal to or greater than the standards set out by the government. These include:

To take ABPs, the site must have the correct permit and biosecurity controls from the APHA (Animal and Plant Health Authority) or similar agency outside the UK, for regulating biosecurity measures and compliance.

Risk assessment, looking at the vectors and pathogens associated with the various categories, must be done.

Part of this assessment must consider bioaerosol monitoring, hazard analysis and critical control points (HACCP) and work techniques that provide collective protection measures to reduce the risk of infecting workers and others.

EXAMPLES

The UK government regulates ABPs through the Animal By-Products Regulations. 70

Regulation (EC) No 1069/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council lays down health rules regarding ABPs and derived products not intended for human consumption. 71

9.20. Develop regulations and standards to limit exposure to hazardous dusts (asbestos and silica dust)

Asbestos is a common building material that is now largely banned in most of the world, but it is still mined and used in some regions. Asbestos, if maintained in a good condition and not disturbed, cut or broken, is not a risk until the fibres are broken and breathed in. Asbestosis is an untreatable and fatal lung condition that has a 20–30-year incubation period. 72 Globally, about 125m people are exposed to asbestos in the workplace. 73

Dusts such as respirable crystalline silica (RCS), commonly caused by cutting brick and stone, can cause silicosis, which is a significant lung disease. It can also cause lung cancer from breathing in the dust.

Each facility must have a policy in place for assessing and controlling the risk from hazardous dusts. The creation of dusts should ideally be eliminated through good planning of work to avoid cutting on-site, although sometimes this may not be practical. Wherever possible, a clear method to implement collective protective measures through extraction at source or wet cutting/coring can reduce dust creation. Clear, documented controls, such as cutting procedures, as part of a management system will set the work method so that risk can be reduced.

EXAMPLES

Guidance on standards, exposure limits and controls measures needed for asbestos and respirable crystalline silica are available from US-OSHA in the US. 74 75

In the UK, asbestos is regulated under the Control of Asbestos Regulations (2012) and an Approved Code of Practice (ACOP), and guidance text has been developed for employers. The regulations set out the legal duties of an employer, and the ACOP and guidance give practical advice on how to comply with those requirements. The regulations give minimum standards for protecting employees from risks associated with exposure to asbestos. 76

9.21. Implement processes to prevent MSDs and manual handling

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are impairments of bodily structures, such as muscles, joints, tendons, ligaments, nerves, cartilage, bones and the localised blood circulation system. MSDs are the most common work-related health problem in many parts of the world, including the European Union. 77 Manual handling of large, heavy and bulky objects can lead to MSDs.

As part of task risk assessment, manual handling should be eliminated, as far as is reasonably practicable. Using the hierarchy of control and the human factors approaches, as outlined above, to suit the job/task, individual and organisation is likely to reduce the impact of workplace ill-health from MSDs.

Regulators must ensure that there is guidance in place for employers to refer to when assessing the risks from manual handling tasks, and data on work-related MSDs should be collated to assess the impact on the workforce.

EXAMPLE

Guidance on how to identify risks and implement controls to minimise MSDs are available from the UK HSE and US-OSHA. 78 79

9.22. Plan safety in design

Safety begins with design. Construction of new AD plants must consider local and national legislation alongside worldwide best practice. Access and egress that will be required for daily operations and infrequent maintenance must be considered at the design stage alongside process safety controls, traffic management and emergency preparedness. Clear arrangements must be in place to cooperate and coordinate between all construction and design processes.

Further details are provided in Pillar 6: Technical and Operational Quality Standards under the “Design and construction standards for AD operations” section.

9.22.1. FEED Process

The Front-End Engineering Design (FEED) process should be conducted following the conceptual design or feasibility study but before the engineering, procurement and construction begins. At this stage the scope of the project should be clarified, all technical documents should be made available and product specifications should be confirmed. This due diligence process should reassure stakeholders that their capital investment is being used wisely. A FEED process will typically include:

- project organisation chart

- project scope

- defined civil, mechanical and chemical engineering

- HAZOP, safety and ergonomic studies

- 2D and 3D preliminary models

- equipment layout and installation plan

- engineering design package development

- major equipment list

- automation strategy

- process flow diagrams (PFD) and piping and instrumentation diagram (P&ID)

- project timeline.

9.22.2. Hazardous substance study and evaluation

Rules for the prevention of major industrial accidents involving hazardous substances are designed to limit the consequences of these accidents to human health and the environment. AD plants contain many substances that are classed as hazardous, and a study must be done to calculate whether these regulations apply to the proposed plant, or after any additions are made to an existing plant. Greater control, regulation and management is required of sites classed as needing control of major accident hazards

EXAMPLES

In the EU, the Seveso III Directive lays down rules for the control of major-accident hazards involving dangerous substances.80

In the UK, large quantities of dangerous substances are regulated through COMAH (Control of Major Accident Hazards) regulations. 81

9.22.3. Risk analysis of process safety

A hazard and operability study (HAZOP) or hazard identification process (HAZID) should be conducted following the initial design stage (See FEED process 9.1.22.1) but before the construction of a plant begins or whenever significant changes are planned. This requirement must be identified during the management of change process. The study must consider the impacts to the process of equipment not operating as planned.

EXAMPLE

Process Safety Management of Highly Hazardous Chemicals standard (29 CFR 1910.119), issued by US-OSHA, contains requirements for the management of hazards associated with processes using highly hazardous chemicals. 82

9.23. Regulate safety in construction

Safety during construction of the plant or any subsequent construction works must be carefully risk-assessed and managed. Construction remains one of the highest risk industries for accidents at work. Clear arrangements must be in place to coordinate all the construction and design processes.

EXAMPLE

The Construction (Design and Management) Regulations (CDM) 2015 apply in the UK and guidance on legal requirements is available from the HSE. 83

9.24. Ensure safety in maintenance

9.24.1. Planned preventive maintenance

Planned preventative maintenance is critical to the safe, efficient and compliant operation of an AD plant. Routine non-intrusive maintenance tasks must be conducted by trained and competent people who have a safe system of work (SSOW) to follow. Intrusive tasks, or those which incorporate specific hazards, must be carried out under a more in-depth safe systems of work, such as a permit to work (PTW) system (see 9.24.2 and 9.24.3).

9.24.2. Safe systems of work

A system of work is a set of procedures detailing how work must be carried out. Safe systems of work (SSOW) are required where hazards cannot be eliminated, and some risk still exists. Development of SSOW includes a process of risk assessment, risk reduction and a management system to control risk.

Adoption of a management system to control risk is generally accepted for routine or repeatable tasks needed as part of the defined safe operation of the plant. These must have a level of risk assessment accounting for design factors, operational considerations and maintenance, to allow safe operation with practical controls in place to protect people and the environment.

For non-routine tasks, an additional PTW system must be used. A PTW is a more formal system stating exactly what work is to be done and when, and which parts are safe. A responsible person must assess the work and check safety at each stage. The people doing the job sign the permit to show that they understand the necessary risks and precautions.

EXAMPLE

Guidance on how to implement a PTW system has been published by the HSE. 84

9.24.3. Non-routine works

Non-routine works at a biogas plant are considered to be any activities that are infrequent or outside normal safe operating practices. These can be:

- breaking primary containment

- planned maintenance

- working at height.

The definition of what is covered under non-routine works is normally the criteria for the application of a PTW system. This is additional layer of administrative control that define safe working methods for a defined period of time, to ensure close control of high-risk, or high potential for risk, works.

9.24.4. Contractor control

Contractors, or those working as specialists coming into the organisation who provide labour and skills for specific tasks, must be:

- assessed for competency before starting the work. Do they have sufficient skills, knowledge, aptitudes, training and experience to do the work safely?

- engaged and communicated with to ensure safety requirements and working methods are appropriately planned and documented

- monitored and adequately supervised to ensure that the work is done as planned

- regularly reviewed regarding their HSE records and incident rates.

9.25. Ensure safety in operation

9.25.1. Risk assessment (routine tasks)

Risk assessment is critical to determining how everyday tasks can be done safely. A good risk assessment should cover the following points;

- clear definition of the specific hazards (things that have the potential to cause harm). These can be broadly categorised as:

- physical

- biological

- chemical

- psycho-social

- ergonomical

- environmental

- identify and define who can be harmed and how can they be harmed as part of this task/process

- evaluation of the risk, hazardous materials labelling / risk matrix / quantitative vs qualitative judgements

- what more can be done to reduce the risk further

- regular defined review (annual) or if something changes that could affect the risk assessment

- must be done by people who are competent to assess the identified process task and hazards.

EXAMPLE

Guidance and templates for conducting general risk assessments are available from the UK HSE. 85

Guidance on conducting job safety analysis is available from the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (CCOHS and US-OSHA. 86 87

9.25.2. Work equipment

Work equipment can be defined as any machinery, appliance, apparatus, tool or installation for use at work.

Work equipment provided must be:

- suitable for the intended use

- safe for use, maintained in a safe condition and inspected to ensure it is correctly installed and does not subsequently deteriorate

- used only by people who have received adequate information, instruction and training

- accompanied by suitable health and safety measures, such as protective devices and controls. These would normally include guarding, emergency stop devices, adequate means of isolation from sources of energy, clearly visible markings and warning devices

- used in accordance with specific requirements, for mobile work equipment.

EXAMPLE

The Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations 1998 in the UK place duties on people and companies who own, operate or have control over work equipment. 88

9.25.3. Personal protective equipment (PPE) and safety devices

PPE and safety devices are an important safety measure in the AD industry. They are the last line of defence on the hierarchy of controls but play an important part in ensuring the safety of the work force, contractors and visitors.

9.25.3.1. Respiratory protective equipment

Respiratory protective equipment can take many forms, from disposable respirators to powered air respirators and contained breathing air systems. When working in the biogas industry, these can provide a lifeline while doing tasks that may introduce hazardous substances, such as dust, gases and other chemicals.

9.25.3.2. Clothing

The selection of protective clothing will vary depending on the nature of the work being done and the climate in which that work is being carried out. Each AD plant must conduct a risk assessment to define the required minimum standard for their workplace and any additional requirements for specific tasks.

9.25.3.3. Head protection

Falling objects can result in major injuries and fatalities; when working at height, a SSOW (9.1.24.2) should be implemented with safe drop zones. However, it is possible for items of plant or loose objects to fall unexpectedly, and this must be assessed when considering which form of head protection should be required on site.

9.25.3.4. Eye protection

AD contains many hazards that can impact the eyes, such as dust, spray, chemicals, biological matter, flying objects and debris. For specialist tasks such as grinding, the level of eye protection required will be defined by the risk assessment and is likely to be of a higher standard than the safety glasses recommended for everyday work.

9.25.3.5. Foot protection

Foot protection is important in any industry where heavy objects are moved around, and this includes AD. Some AD plants may have uneven ground that requires a level of ankle protection, or chemicals from which footwear can provide protection. Protective footwear can be worn to protect the user from sharp objects that may be found in the waste processed, and from any heavy objects that come into contact with the foot.

Footwear must be easy to clean and disinfect in plants that handle ABPs. The precise requirements for foot protection will be defined by risk assessment of the workplace and work tasks to be done.

9.25.3.6. Hand protection

Gloves are an important protection measure when working in AD. Specialist cut-resistant or chemical-resistant gloves may be required for specific tasks; however, a minimum level of hand protection must be made available to protect workers from skin issues such as contact dermatitis, diseases such as Weil’s disease, and biological contamination from waste products.

EXAMPLE

Further guidance on selection and use of PPE is available from the UK HSE and US-OSHA. 89 90

9.25.4. Gas safety

Gas safety is one of the major risks when running an AD plant. All process safety systems, such as pipelines vessels and processing equipment, must be maintained to the design standard requirement. To protect workers, several types of gas detection systems are available, as detailed in sections 9.25.4.1–9.25.4.3.

9.25.4.1. Personal gas monitors

AD plants are designed to create biogas, but biogas can be dangerous if personnel are exposed to it. Biogas mainly comprises of around 50–70% methane (CH4), 30–45% carbon dioxide (CO2) and smaller amounts of nitrogen (N2). It also may contain traces of hydrogen sulphide (H2S), which can cause illness or death if exposed to it.

Fully calibrated personal gas monitors are important in ensuring staff are alerted to the presence and level of any dangerous gases. Standard gas sensors would measure for:

- the lower explosive limit (LEL) for methane or other combustible gases

- H2S to prevent personnel exposure

- carbon monoxide (CO2) for unburnt fuels

- Oxygen (O2), as this can be reduced or enriched in certain anaerobic atmospheres resulting in unconsciousness.

Gas monitors may be alarm only, fully remotely monitored or have additional functions such as lone-working protection measures. 91

Depending on the feedstock mix, ammonia (NH2) may also be present, which may require additional personal monitoring depending upon the outcome of risk assessment.

There are many proven devices that can be used as gas detection. Which to use should be based on a suitable business case, incorporating lifecycle costs, calibration costs, repair and servicing costs.

All workers must be trained on the risks of gas, especially the effects of H2S, O2, CO and CO2.

9.25.4.2. Fixed and portable gas monitors

Fixed gas monitors are useful in areas where exposure to the gases mentioned previously are likely to be present and other gases such as NH3 may also be present, e.g. in areas with digestate and separated fibre.

Fixed gas detection monitors must be serviced and calibrated regularly and can be designed to alert personnel externally to the specific area where dangerous gases are present, thus allowing them to have the area made safe before they enter. Most fixed gas detection systems store data that can be interrogated to identify any peak gas emissions.

Fixed systems must be built into the design considerations of the plant, based on which areas are likely to have gas accumulation that could cause harm. Suitable alarms and alerts must be set up to enable people to evacuate areas where gas is present.

Portable gas detection may be needed for construction-phase works, or where high-risk works such as breaking containment is needed. Portable gas detection can be organised to ensure that adequate monitoring is in place.

EXAMPLE

EU-OSHA provides guidance on gases and vapours in the work environment. 92

9.25.4.3. Local exhaust ventilation

Local exhaust ventilation systems (LEV) may be required in specific areas of an AD plant, such as waste storage areas, laboratory areas with dry matter ovens, or other areas where emissions of chemicals or compounds must be extracted at source to prevent harm to personnel. They may also be required when conducting specialist works such as welding.

EXAMPLE

The HSE has a wealth of resources on LEVs, including INDG408, a guide to buying and using LEVs. 93

9.25.5. Pressurised systems

A pressure system is one that contains or is likely to contain a fluid over 0.5bar. These systems can cause severe injury if not handled properly and so must be closely regulated.

Pressurised systems are found in many areas of an AD plant; they are often air receivers used to store compressed air that operates pneumatic equipment such as valves.

Boiler and steam heating systems, heat exchangers and refrigeration plant, pipework and hoses, pressure gauges and level indicators can all be classed as pressure equipment if the system contains fluid over 0.5bar.

9.25.5.1. Inspection

Pressure systems must be inspected in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions and local guidelines.

9.25.5.2. Maintenance

Maintenance of pressure systems must be planned and conducted routinely by a competent, qualified engineer. Any defects must be reported to the person in charge immediately so this can be addressed.

9.25.5.3. Record keeping

AD plants must keep a record of all pressure systems and ensure these are regularly serviced and maintained by a competent person.

EXAMPLE

In the UK, Pressure System Safety Regulations 2000 (PSSR) impose duties related to pressure systems for use at work and the risk to health and safety. 94

Compressed gases and equipment and pressure vessels are addressed in specific US-OSHA regulations and standards for health and safety. 95 96

9.25.6. Process machinery safety

9.25.6.1. Product certification and marking

There are a number of international harmonised standards for trading into economic areas. These harmonised standards generally have requirements on safety, environmental and quality that need adherence to, so that products can be certified as meeting these requirements.

EXAMPLE

CE marking in Europe, UL labels and marking in North America, the CCC system in China, and GOST and EAC marking in Eurasia provide equipment safety certification for these regions. 97 98 99 100 101

9.25.6.2. Manufacturing standards

The manufacturer of equipment has a duty to ensure that equipment is fit for purpose, safe to use and has clear instructions for the end user. Each marking scheme will have requirements related to the type of product sold.

9.25.6.3. Importing machinery

When importing machinery, the end user must assess its suitability and safety, checking that guarding and safety features are adequate and meet operational requirements and national regulations. Changes or upgrades to equipment must trigger a risk assessment review to assess their impact. A hazard and operability study (HAZOP – see 9.22 Plan safety in design ) is a useful tool to identify and understand any additional risks posed, and plan for adequate changes to be made for additional controls.

9.25.7. Vehicle safety and traffic management

Vehicle safety and traffic management play a critical role in ensuring the safety of mobile plant operators and pedestrians. Vehicles used in the AD industry include cars for business driving and mobile plants, such as forklifts, telehandlers and loading shovels. Many sites will have deliveries and/or collections from refuse-collection vehicles, skip lorries, tippers, articulated lorries and tankers.

New sites must consider the safest routes, such as one-way systems, at the planning stages, and existing sites must review their traffic management plan to ensure that safe segregation of vehicles and pedestrians is maintained.

Mobile plant drivers must be trained and competent to operate the machines safely, and the machinery must be subject to regular safety checks, inspections and servicing to ensure it is safe to operate.

EXAMPLE

EU-OSHA have published an e-guide on good practices for managing work-related vehicle risks in the EU. 102

Guidance is also available from the UK HSE on the use of mobile plant and vehicles, site safety and traffic management. 103 104

9.25.8. Confined Spaces

A confined space is a space that is enclosed, or largely enclosed, and poses a reasonably foreseeable risk such as fire, explosion, loss of consciousness, asphyxiation or drowning.

In the US, between 2011 and 2018, 1,030 workers died from occupational injuries involving a confined space. The annual figures in the US range from a low of 88 in 2012 to a high of 166 in 2017. 105

Confined spaces on AD plants range from the obvious, such as digesters and fermenters, to the less obvious, such as hoppers, condensate pits, small tanks and manholes.

To successfully work in a confined space, the following must be in place or achieved:

- a strict SSoW in place

- risk assessment

- emergency procedures

- competency of individuals

- special training requirements

- permit to work

- monitor and review

- supervision

- further mitigation measures may be required depending on the hazard and control measures in place.

EXAMPLES

Regulations and guidance on working in confined spaces are available from the UK HSE and OSHA in the US., 106 017

One example of a confined space risk assessment by Alcumus is shared here. 108

9.25.9. Fire safety and risk

The starting point for fire safety on AD plants is a fire risk assessment. This must be conducted by a competent person and include all potential fire risks, including mechanical, electrical, accidental and malicious.

Fire detection, such as smoke/heat detectors, laser or Very Early Smoke Detection Apparatus (VESDA) systems should be fitted throughout the site and connected to an alarm system. Fire extinguishers must be made available in line with the risk assessment, and staff must be trained on their duties in the event of a fire. When creating an emergency response plan, it can be useful to consult the local fire and rescue service. This is required on all sites that store hazardous substances.

EXAMPLES

Fire safety regulations, standards and guidance on how to comply with them are available from US-OSHA. 109

Guidance on how to ensure fire safety in the workplace and on requirements for fire risk assessment are available from the UK HSE. 110

9.25.10. Explosion safety and risk

The starting point for explosion safety and risk assessment must be a risk assessment of dangerous substances and explosive atmospheres.

Biogas is considered an explosive substance as well as a toxic one, and as such rigorous controls must be put in place for any activities that may generate heat or sparks. Many sites also store other explosive substances such as propane for gas upgrading, or other specialist substances; these should be clearly controlled and the areas demarcated.

EXAMPLES

Directive 99/92/EC establishes the minimum requirements for improving the safety and health protection of workers potentially at risk from explosive atmospheres (ATEX). 111

In the UK, explosion safety is regulated under the Dangerous Substances and Explosive Atmospheres Regulations 2002 (DSEAR). Guidance on how to comply and implement control measures are available from the UK HSE. 112

9.25.11. Emergency planning and response

Emergency planning and response plays a significant role in the operation of an AD plant. Ensuring that staff are aware of the risks (what may go wrong) and the impacts they may have is the first step in ensuring they can control them. If things do go wrong, then the site must have a plan for how it will respond.

Emergency scenarios must be compiled and regular exercises conducted to ensure staff have a chance to practise their response in the event of a real emergency.

9.25.11.1. Key elements to include in emergency procedures

Consider what might happen and how the alarm will be raised. Do not forget to account for night shifts, weekend operations and times when staff are off-site and premises locked, e.g. holidays, as the plant remains operational 24/7.

- Plan what to do, including how to call the emergency services. Help them by clearly marking your premises from the road. Consider drawing up a simple plan showing the location of hazardous items.

- If you possess twenty-five tonnes or more of dangerous substances, you must notify the fire and rescue service and put up warning signs.

- Decide where to go to reach a place of safety or to get rescue equipment. You must provide suitable forms of emergency lighting.

- You must make sure there are enough emergency exits for everyone to escape quickly and keep emergency doors and escape routes unobstructed and clearly marked.

- Nominate competent people to take control (a competent person is someone with the necessary skills, knowledge and experience to manage health and safety).

- Decide which other key people you need, such as a nominated incident controller, someone who is able to provide technical and other site-specific information if necessary, or first-aiders.

- Plan essential actions such as emergency plant shutdown, isolation or making processes safe. Clearly identify important items such as shut-off valves and electrical isolators.

- You must train everyone in emergency procedures. Do not forget the needs of people with disabilities and vulnerable workers.

- Work should not resume after an emergency if a serious danger remains. If you have any doubts, ask for assistance from the emergency services.

EXAMPLE

Guidance on how to develop emergency procedures is available from the UK HSE and US-OSHA. 113 114

9.25.12. Lifting equipment and accessories

Lifting equipment and accessories are widely used in AD plants; from installation to maintenance and everyday movement of feedstock and parts, lifting equipment is a critical part of the plant, but it must be used safely. Lifting equipment must be inspected before use and subject to regular, thorough examinations; it must be identifiable by an individual marker; and a register must be kept of all lifting equipment and accessories on-site.

EXAMPLE

Guidance on how to safely undertake lifting operations is available from the UK HSE, the Lifting Equipment Engineers Association and EU-OSHA. 115 116 117

9.25.13. Working at height (and around water)

Falling from height is the leading cause of workplace fatalities in the UK. Working at height includes working from ladders and platforms (including mobile elevated work platforms), but also any place where, if there are no precautions in place, a person could fall a distance that would be liable to cause personal injury. This distance does not necessarily need to be high to be counted as working at height.

Handrails, barriers, edge protection, fragile roof protection and work restraint systems are all examples of controls that could be put in place as a result of a risk assessment for working-at-height activities.

Falling objects are a risk for those who may be working below a working-at-height project; exclusion zones, netting and edge protection alongside tethered or secured tools must be considered as part of the risk assessment.

Working around water (or digestate) lagoons or other open areas of water presents a risk of drowning; risk assessments should be conducted to ensure that access is restricted, controlled and conducted in a safe manner. Rescue plans must be agreed and communicated to all people who may be in or around the working area.

EXAMPLES

Guidance is available on working at height from the UK HSE, Health Authority – Abu Dhabi, US-OSHA and EU-OSHA. 118 119 120 121

Guidance on working on/near water is available from CCOHS. 122

9.25.14. Working with or near electricity

Working with electricity is common on AD plants because of the array of equipment used to keep the site functioning. Everyone working on electrical equipment must be trained and competent to do so.

High voltage (HV) electrical work will require specially trained workers.

EX-rated equipment for use in explosive atmospheres requires electricians with additional training to ensure they understand the specialist requirements of this equipment. CompEx-trained electricians are those with additional qualifications that show competence for working on EX equipment.

Staff and other contractors working near electricity, such as any works near overhead power lines or underground connections, or in proximity to HV equipment, must be made aware of the risks and set safety distances must be adhered to.

EXAMPLE

Regulations, standards and guidance on working safely with or near electricity is available from the UK HSE, US-OSHA, the Department of Energy, Abu Dhabi, and EU-OSHA. 123 124 125 126

9.25.15. Excavations

Excavation work must be undertaken carefully and a Permit To Work (PTW) system must be used to avoid contact with underground services and to ensure that any excavations are continually made safe to avoid collapse. (see 9.24.2 and 9.24.3).

EXAMPLE

Guidance on how to ensure excavation work is completed safely is available from the UK HSE. 127

9.26. Climate change adaption risk assessment

Climate change affects the operations of AD plants worldwide and, therefore, a climate change adaptation risk must be conducted for every facility to at least the standard noted below.

Regulators must require all AD plants to undertake a climate change adaption risk assessment to understand the impact of climate change on the facility, including severe temperatures, drought, flooding and other sudden changes in weather that could affect the safety of the plant or its ability to operate.

EXAMPLE

The UK government has published resources for conducting a climate change risk assessment. 128

9.27. Enforce consequences on failure to comply

Failure to comply with laws and regulations can lead to criminal and civil legal proceedings against those in authority, as well as fines and penalties for breaches of legislation. Additionally, there is the reputational damage caused by these events. It can also lead to additional costs for regulator charges.

There are also layers of costs to business, such as loss of production, increased insurance premiums, employee time off, clean-up and operational restart costs. There is a compelling case that good health, safety and environment management is good financial management.

EXAMPLE

In the UK, the Environment Agency published examples of incidents of UK HSE violations at biogas facilities in the UK that were followed by fines and corrective actions. 129

9.28. Minimise waste generation on-site